On a recent trip to Nicaragua I documented the incredible work Paso Pacifico is doing to protect sea turtles... and learned the most mind-boggling fact about sea turtle shells. (hint: it's glowy)

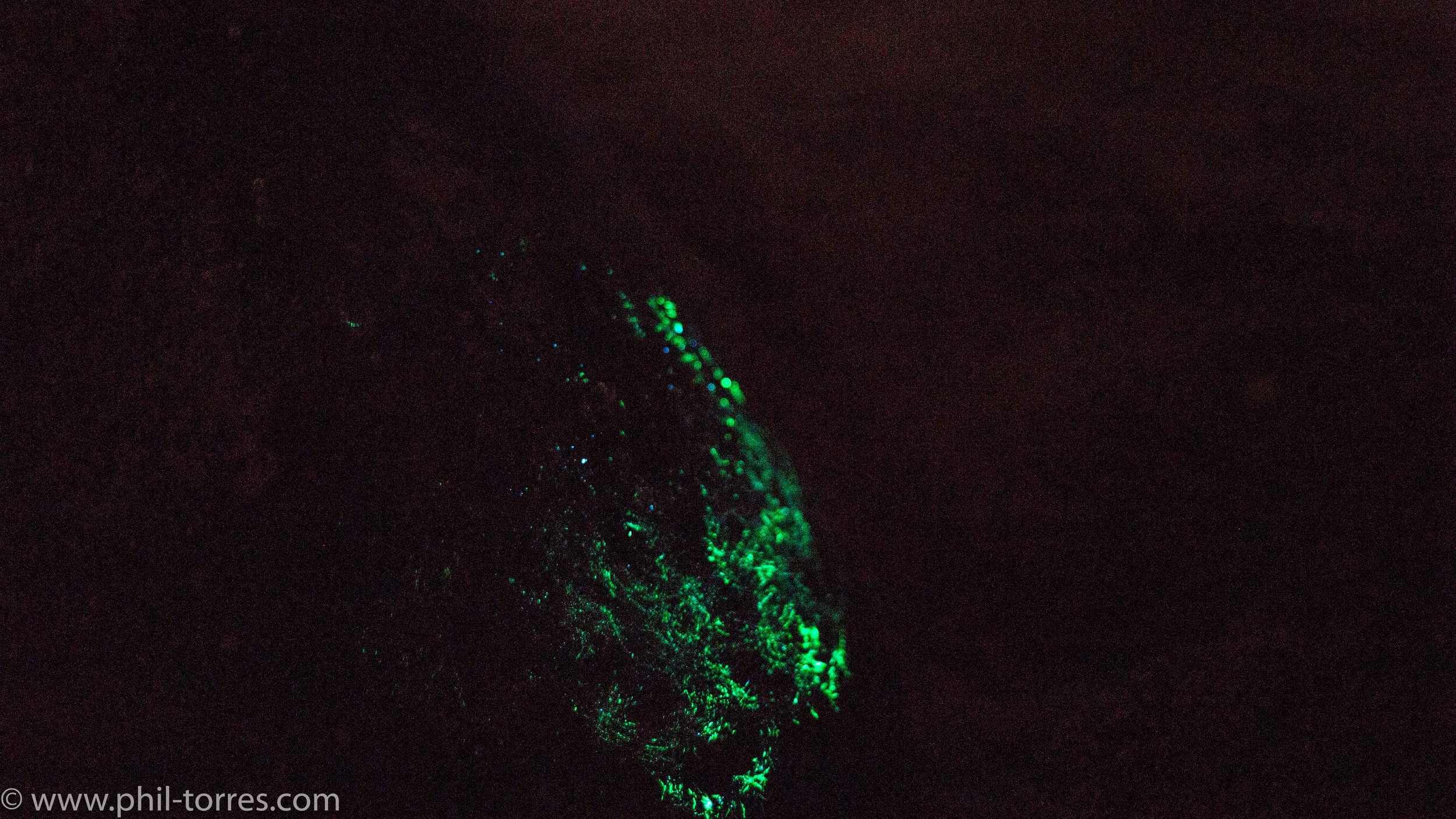

A long-exposure photo showing the zig-zag pattern the park ranger wiped with his finger on the sea turtle's shell. My guess? Bioluminescent phytoplankton accumulation.

A similar glow is seen along the shore when you step near where the waves break- for some reason these plankton are highly concentrated on the turtle's shell.